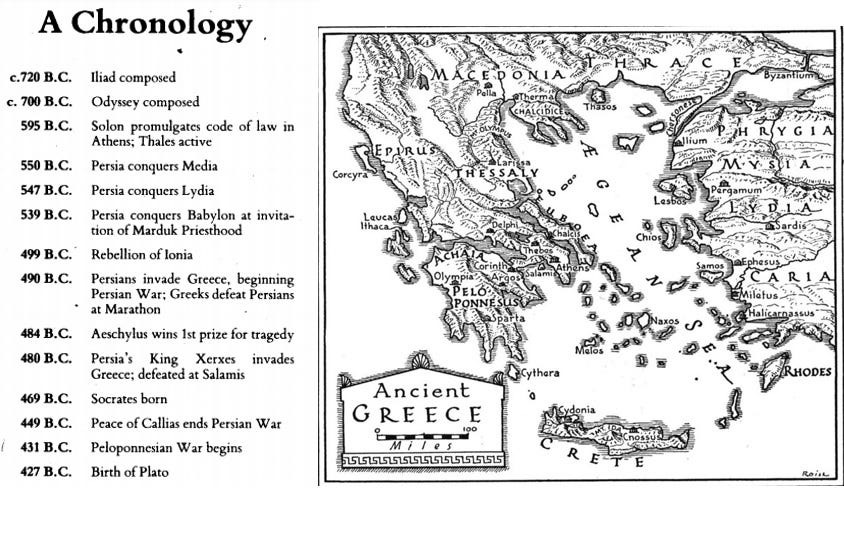

Homer’s great poems that are left to us today, The Iliad and The Odyssey, describe the events of the Trojan War and its immediate aftermath, events which marked the descent of Greece into a Dark Age. Following the Trojan War, c.1190 BCE, the civilization of mainland Greece collapsed, written language was lost, and cities disappeared.

During this period, Greece suffered an almost complete loss of its history. To this day, we do not know much of what Greece was before and during this Dark Age.

The Iliad and The Odyssey, written around c.720 BCE heralded the reversal of the collapse, and the beginnings of Classical Greek culture.

In Plato’s Timaeus, Solon (630-560 BCE) visits the Egyptian priests of Neith to discuss Greece’s history, for unlike the Greeks, the Egyptians had done well in preserving a record of their history for over centuries. The Egyptian priests say to Solon, that this is not the first time that Greece had nearly lost all record of their history, that the Greeks had been an advanced civilization before this last deluge, and that there had been many deluges prior, each time wiping all record of the previous civilization. A very aged priest tells Solon, in Plato’s Timaeus, that several centuries earlier, Athens had been in conflict with the great power of Atlantis, which was then destroyed in a catastrophe.

The Egyptian priests recount to Solon how the Greek people had gone from an advanced civilization to being like children every time there was a natural calamity.

Solon (630-560 BCE) is considered the greatest of the seven sages of Greece, and is famous for writing the code of laws in Athens and establishing the Republic of Greece, which laid the foundations for how government and society would be organized for the next 2500 years.

Among Solon’s economic reforms included the first debt moratorium in history, which saved thousands of farmers from bankruptcy. He outlawed the sale of free men into slavery to pay their debts, and encouraged craftsmanship and industry knowing that these were among the greatest expressions of human achievement. This propelled Athens to become a world leader in the arts and sciences.

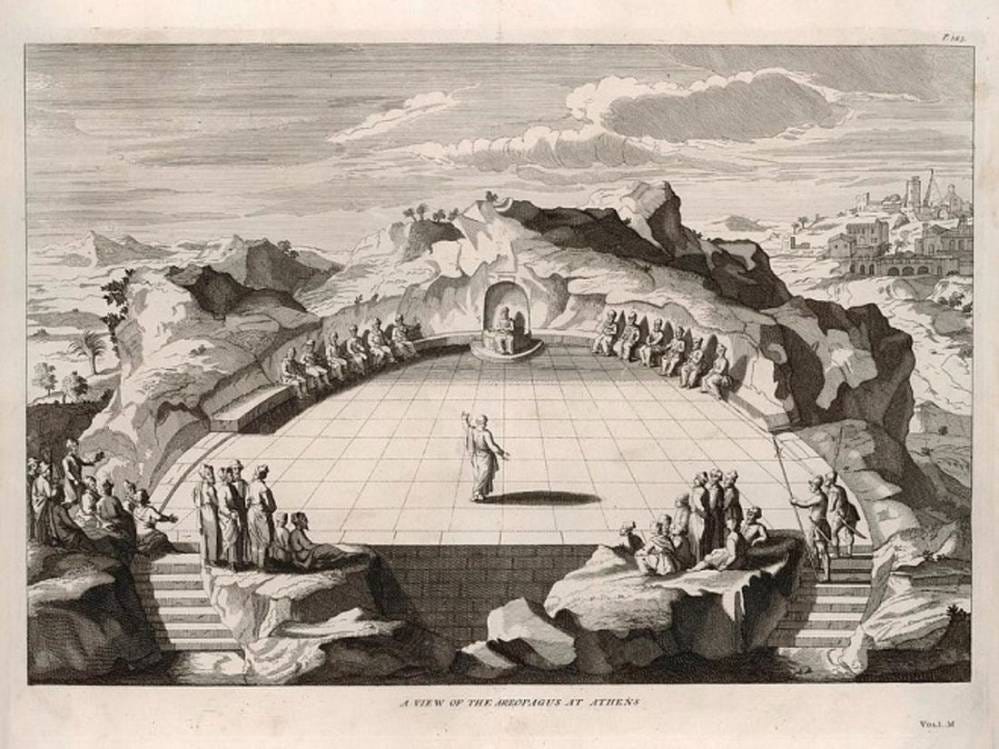

Solon also set up the Council of the Areopagus, which was made up of aristocrats, were selected based on their merit, and served the council for life. The Council of Areopagus played a major positive role in Greek politics (more on this shortly).

It is said that with these laws in place, Solon left Athens for 10 years, since the people had agreed to give the laws this amount of time, and visited Egypt among many other places. Plato, would make a similar trip two hundred years later.

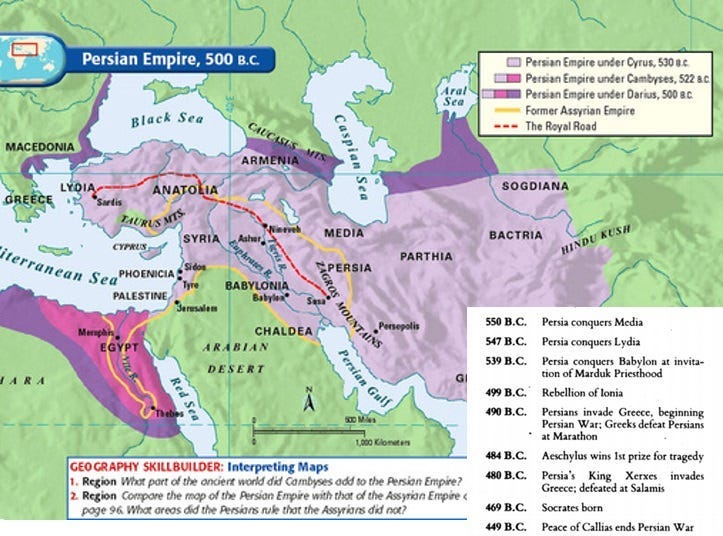

Cyrus the Great (unknown-530 BCE) from around 550 to 539 BCE led a military campaign that is recognized as the reunification of the Iranian people, but also entered the territories of Lydia and Ionia. In these areas considered to be the reunification of Iran, he united the tribes, set up a common language and promoted the sciences and industry, and thus contributed much as a builder of these cities.

The reason why he went into Lydia and Ionia is a bit of a controversial case because King Croesus of Lydia had basically become convinced by the Assyrian Empire and also the priests of the Temple of Delphi that he would be victorious in an attack against Cyrus the Great, despite Cyrus being ready to leave Lydia and Ionia alone.

Cyrus the Great appears to be an exception to what followed him afterwards during the reigns of Darius, Xerxes, and Artaxerxes who led the Persian Empire and who we will discuss further later on. [Military Campaign of Darius I 521-486 BCE, Xerxes I 485-465 BCE, Artaxerxes I 464-424 BCE.]

Babylon was the last conquest of Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE.

According to Charles Tate, author of “The Truth About Plato,” the Babylonian priesthood (led by the priests of Marduk) seeing what Cyrus the Great was accomplishing, thereupon decided to open the doors of Babylon to him. They did this partially because they knew they would not be able to resist him anyway, but also because they thought that they could use him.

When Cyrus enters Babylon, he slaughters the Babylonian King and all those considered loyal to the King. But the Marduk priests were allowed to go about their daily rituals as if nothing had happened. This was because they had made an agreement with Cyrus the Great.

Thus ended the reign of the Babylonian Empire (1895 – 539 BCE). However, as often occurs with the collapse of a powerfully ancient empire, much of the seed of that empire was transferred over to a new host.

The Marduk priesthood was ancient, and rose to prominence during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE) and continued to be venerated in the city throughout the time of Persian rule.

The Marduk priesthood always believed in the right to enslave and brutally tax the populations of Mesopotamia.

It is not clear if Cyrus the Great was aware of what the Marduk priesthood was as a global force of evil, nevertheless, he did officially recognize the god Marduk and would publicly worship him during his stay in Babylon.

However, to put things into balance, no king appeared to be free of this form of control. No Babylonian king ever made war, or peace without first consulting the oracles of the Marduk Temple. This was the exact system later put in place at Apollo’s Temple of Delphi in Greece. In fact, Marduk is the equivalent to Zeus and Apollo in Greece and Horus in Egypt, first originating in Babylon. And temples were set up with these priesthoods under this common network.

Not even King Leonidas with his legendary force of 300 against Persia was able to avoid paying a visit to the Cult of Delphi before setting on to the Battle at Thermopylae in 480 BCE.

One of the most famous prophecies made by the Cult of Delphi, according to the ancient historian Herodotus, was to King Croesus of Lydia in 550 BCE. King Croesus was a very rich king and the last bastion of the Ionian cities against the increasing Persian power in Anatolia. The king wished to know whether he should continue his military campaign deeper into Persian Empire territory.

According to Herodotus, the amount of gold King Croesus delivered was the greatest ever bestowed upon the Temple of Apollo. In return, the priestess of Delphi, otherwise known as the Oracle, would spout nonsensical babble, intoxicated by the gas vapours of the chasm she was conveniently placed atop. The priests would then “translate” the Oracle’s prophecy.

King Croesus was told as his prophecy-riddle, “If Croesus goes to war he will destroy a great empire.” Croesus was overjoyed and thought his victory solid and immediately began working towards building his military campaign against Persia. Long story short, Croesus lost everything and Lydia was taken over by the Persians.

It turns out the prophetic riddle was not wrong, but that Croesus mistook which great empire would fall.

The Cult of Apollo thus destroyed the Greek-allied kingdom of Lydia, misleading King Croesus. It also derailed Ionia’s resistance to the Persian invasion, countered Athenian intervention to aid Ionia against Persia, attempted to sabotage Greek resistance in the Persian War, and encouraged the suicidal Peloponnesian War launched in 434 BCE.

The priests of Delphi were also spreaders of occult superstition.

For instance, whenever the populace would be mobilized towards a certain action, such as the support for the Ionian uprising against Persia (more on this shortly), the Cult of Delphi said that terrible things were going to happen if the Athenian people supported this. The people were told that Apollo would be very upset and that plagues would be unleashed on the people if they supported such a cause.

The Apollo temples were also the wealthiest banking centers in the Mediterranean world. They would finance military campaigns, politicians, and the careers of generals who could be used to advance their agenda.

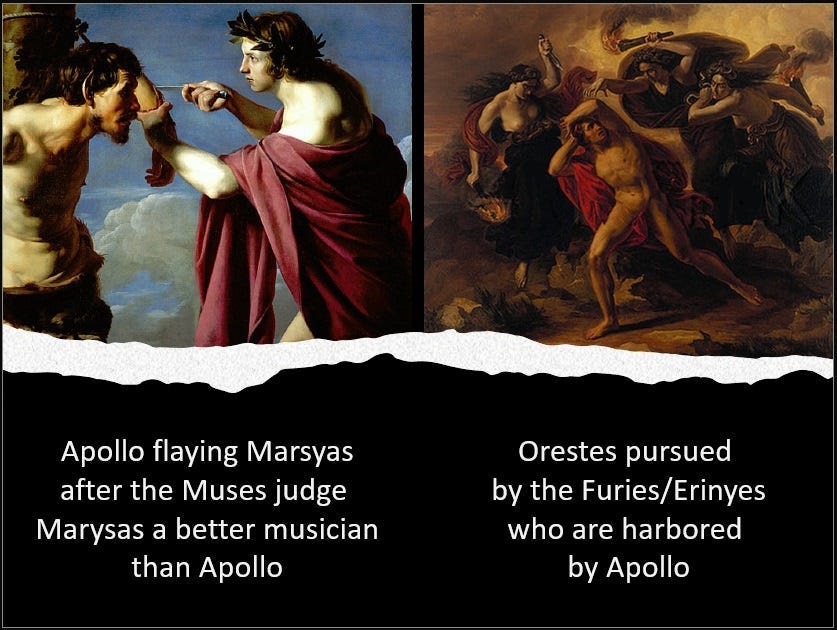

Two stories that give us an idea of what sort of god Apollo was, are those of Marsyas and Orestes. In one story, Marsyas and Apollo enter a music competition that is judged by the Muses. Marsyas, a Phrygian Satyr, was an expert player of the double fluted instrument known as the aulos.

Apollo is known for playing the lyre. The Muses decide that Marsyas is the better instrumentalist, however, in the final round Apollo sings while playing the lyre and the Muses are won over and ultimately favor Apollo.

Since the victor decides what they wish to do to their competitor, Apollo decides to flay (peel the skin off) Marsyas alive, for he was technically the better player and Apollo was so jealous that he had Marsyas slowly tortured to death.

The other well known story is by Aeschylus (524-456 BCE), in his famous Orestes trilogy. [I will go into a little bit of the political and artistic role of Aeschylus in Greece shortly.]

In the Orestes story, there is a curse that follows Agamemnon (the General of the Greeks) back from the Trojan War, since it was not a Just war.

The war started when Menelaus’s wife Helen (known as one of the most beautiful woman in the world) was seduced by Paris, a prince from Troy and ran off with him. Thus to save face, Menelaus (the brother of Agamemnon) decides Greece must go to war with Troy, a war which lasted anywhere between ten and twenty years.

In order to have good weather for the voyage, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia to the gods. This crime sets a terrible cycle of an-eye-for-an-eye retribution that would go on for years.

Orestes is the son of Agamemnon and the story focuses on this cycle of vengeance and destruction. Creatures known as the Erinyes (aka: Furies) torment and hunt those who have committed a crime and are harbored in the temples of Apollo, who is the god of distance, death, terror, and awe.

In Aeschylus’ story, the resolution to this ongoing vicious cycle of destruction is the creation of the Council of the Areopagus, which was the council that had been set up by Solon earlier. The Erinyes are able to find their place in a more noble form of natural law and secondary to the Council of the Areopagus, which functioned like a court of law with Athena as its symbolic head.

***

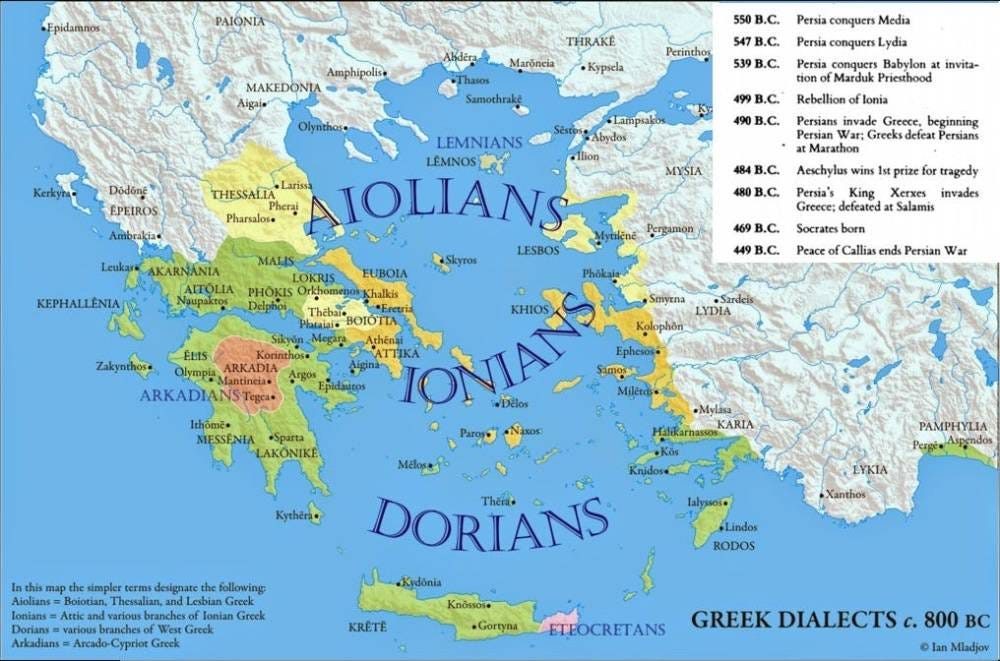

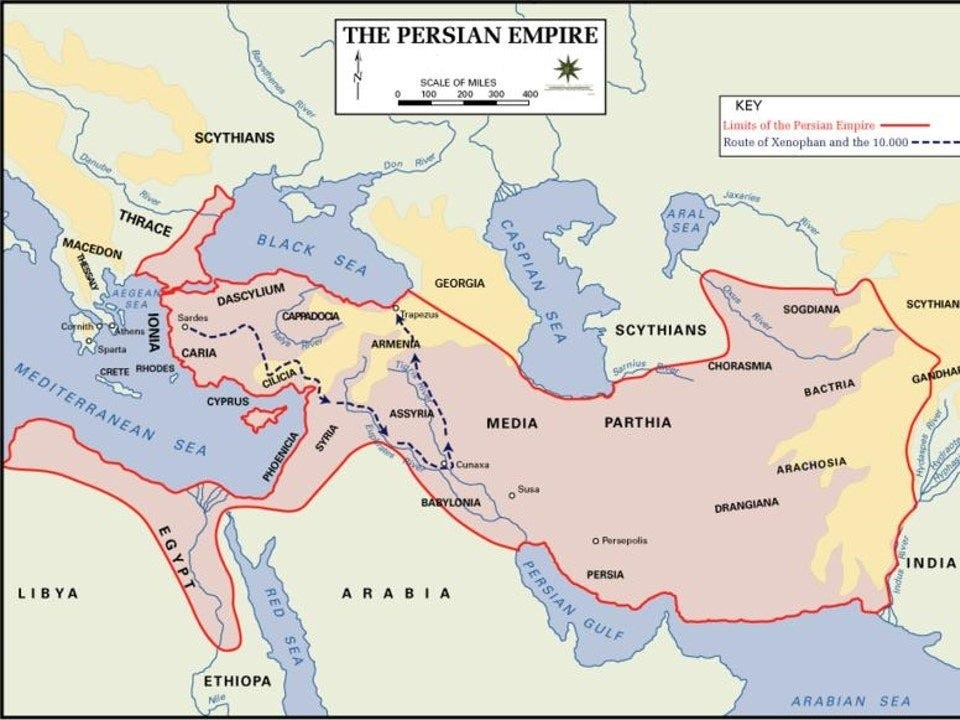

By 499 BCE there was the Ionian Uprising against Persia. As you can see in the map the Ionians are in the center, and the rebellion is occurring on the right side of the map in Asia (with the left side being mainland Greece).

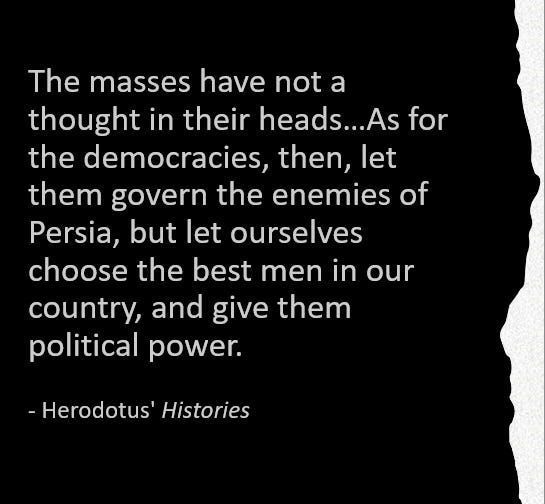

After Solon, there was a period of tyrants who ruled Athens followed by the period of the Greek democrats. These Greek democrats were the force most controlled by not only the ever-abundant Persian coin, but also Persia’s intelligence apparatus. Hold in mind that Babylon was still at the center of the Marduk, Apollo, Horus network.

In 499 BCE, anti-Persian forces revolted against King Darius I. The leader of the revolt, Aristagoras of Miletus traveled throughout Greece seeking support for the rebellion. In Athens, his call was heeded with the city sending ships and heavily armed Greek soldiers resulting in many military successes.

After about a year, Greek democrats in Athens began saying that they should not be supporting the Ionian Uprising because they were led by Ionian aristocrats, thus Greek democrats should not be supporting these landowners who, it was claimed, only cared for their own interests. Unlike the Athenian Democrats, these “corrupt” Ionian aristocrats were against the rule of the Persian Empire and were for the independence of the Greek states.

The Cult of Delphi added to this mob frenzy by spreading superstition that bad things would happen if the people continued to support the Ionian rebels.

As a result of the loss of Athenian support, the men of Miletus were all butchered, the boys castrated to serve the Persian Empire as eunuchs and the women were either forced to become brides, brought to harems or forced to fend for themselves.

When Mardonius, Persian General, in 492 BCE (son-in-law to Darius I) led an armada of 600 ships against Ionia, rather than replace Ionian aristocrats with Persian overlords, Mardonius instead placed Greek democratic stooges into power, as they were considered a much more effective control on the population.

The Council of the Areopagus, the traditional leadership of Athens established by Solon, consisting of aristocrats, also started to come under attack from the Athenian democrats.

And so there was a fight as to what the future of Athens was going to be, whether they were going to be a free people or subjects of an empire.

Cleisthenes, the first democratic leader of Athens in 510 BCE attained power not by any popular movement or class struggle but by the financing of the Cult of Apollo. Cleisthenes’s Alcmaeonid family went on to dominate the Athenian democracy for nearly one hundred years with the backing of Delphi.

In 507 BCE Cleisthenes voluntarily sent to Persia the traditional tokens of submission, earth and water, marking the first official contact between Persian imperialism and Greek democracy with a promise of Athen’s vassalage to King Darius I.

Years later, King Leonidas of Sparta also received envoys from Persia asking for these same tokens of submission. According to legend, King Leonidas exclaimed “You want earth and water?” and threw the entire Persian envoy to their deaths down a deep well.

This led to the legendary battle of King Leonidas’ 300 men at the Thermopylae in 480 BCE where they fought an incredible resistance to the onslaught of the Persian Empire, and are remembered as heroic warriors against the rule of tyranny to this day.

During this period, Athenians would also have their share in legendary battles against the Persians with the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, and the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE. However, despite their legendary victories against incredible odds, Athenian democrats were able to move the political foment to an increasingly pro-Persian stance under the government of the Cleisthenes’ Alcmaeonid family (whose members also included Pericles and Alcibiades).

The historian Herodotus (484-425 BCE) offered the following account of Persia’s motives for establishing so-called democracies to rule over its satrapies.

And thus, Greek democracy did not have a lot of respect from Herodotus either, who lived during the time of Xerxes.

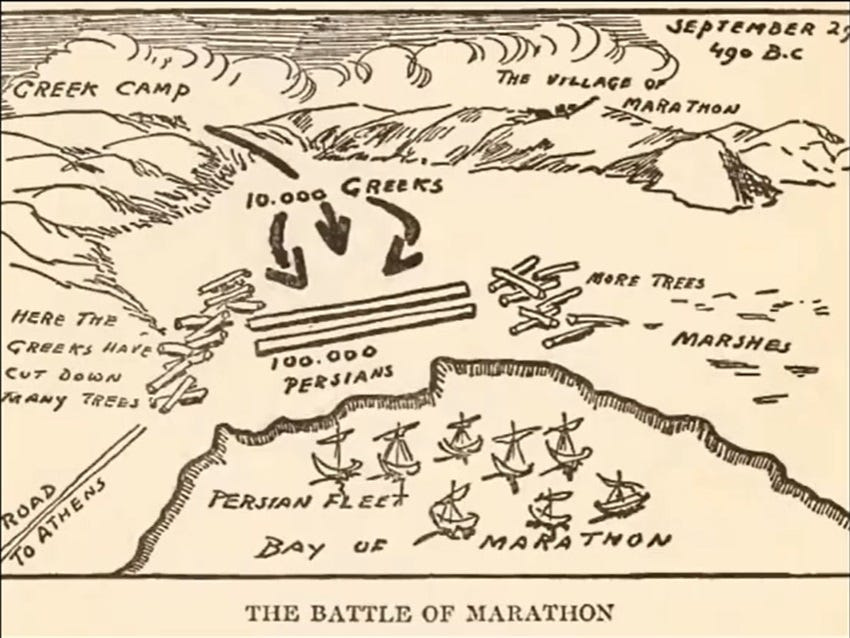

King Darius I (550-486 BCE) was successful in crushing the Ionian revolt and so he thought it was going to be a piece of cake to take over the Greek mainland.

The Areopagites who were made up of the Athenian aristocracy, described themselves as the party of the Beautiful and the Good [“Beautiful” in this case, referring to that which pertains to the soul].

To the Areopagites, Greeks did not live in a nation or an empire, but in city-states, independent communities clustered around a city center.

Each city-state had different laws, worshipped different gods but were unified by the common Greek language which created the bedrock of their common culture under Homer.

One of the tools used by the Greek city states against the threat of Persia, under the direction of the Council of the Areopagus, was found in classical Greek tragedies and the Greek tragedy competitions. These competitions were held between three different playwrights (selected half a year before), who were required to compose three tragedies and one satyr play each. The Greek tragedy festivities were second only to the Athletic competitions and were deeply influential on the Greek culture.

In 493 BCE, Phrynichus staged his drama Capture of Miletus on the Ionian Uprising (about the population that was slaughtered by the Persians). The drama carried a strong warning to mainland Greeks that the defeated Ionians’ fate would soon be their own if they did not prepare to expell the Persians.

The leaders of the democracy banned it, and this became the only play ever to be censored in the history of the politically volatile Greek theater because it “called too strongly to mind the suffering of the people.” However, likely the real reason why the play was censored, was due to the fear that it would instigate an uprising by the Greek people against Persia’s increasing control over their lives.

Another famous playwright who would follow Phrynichus is Aeschylus, known as the greatest Greek tragedian.

Aeschylus would write the Orestes trilogy, as already discussed and also wrote The Persians, recounting the heroism of the Greeks in defeating Darius I at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE.

As already mentioned, Darius I was very cocky after subduing the Ionian Uprising and figured the conquering of mainland Greece would not be difficult. The Battle of Marathon was the first battle the Greeks fought against Persia and it was a humiliating defeat for the Persian Empire, where 10,000 Greeks were able to defeat 100,000 Persians.

It wouldn’t be for another ten years before Persia would try to attack mainland Greece, this time under Xerxes in 480 BCE.

Xerxes had defeated King Leonidas, but that was only because Leonidas could only organize three hundred men to follow him, since Sparta was also going through its own problems with influential Spartan politicians bought with Persian coin. If this sort of corruption had not taken hold and King Leonidas had his full army, they would have undoubtedly beat the Persian onslaught.

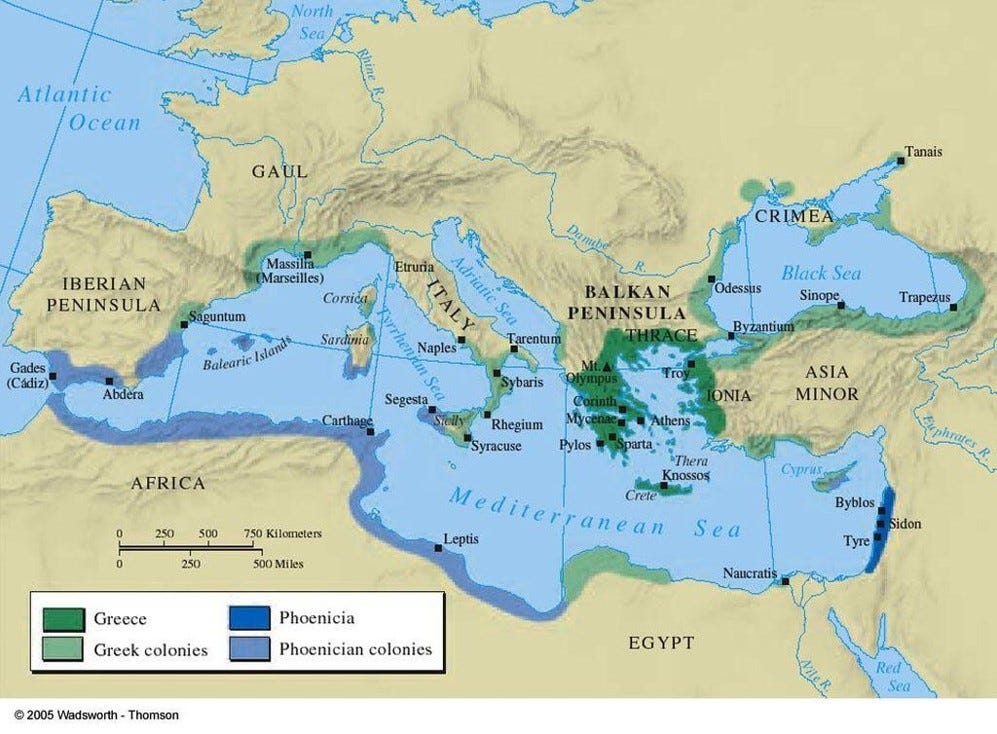

The Battle of Salamis would again deal a humiliating defeat to the Persians in 480 BCE. As the story goes, the Phoenicians, who had been conquered, were manning the ships of the Persian Empire and met the Greek ships, only to immediately defect to the side of the Greeks.

The Persians written by Aeschylus was again to rouse the spirit of the Greek people to resist being ruled as a vassal state by the Persians. The play taught the people that there was no need to bow down to an inferior system that was based on subjugation and plunder.

How greatly the victory of Marathon effected the political morale of the Greeks can be seen from the fact that Aeschylus’ chosen epitaph forty years later written on his tomb stone, said nothing about his plays which guaranteed his immortality or about his lifetime as a political organizer for the Areopagites but only that he had fought at Marathon.

With this victory, Greece was now on the offensive and was preparing to take back Ionia and assist in the liberation of Egypt. This force for the first time united the two most powerful cities in Greece, Athens and Sparta, in an alliance known as the Delian League, founded in 478 BCE.

From c.461- 429 BCE Pericles would be the head of Athenian democracy. Falsely remembered as the architect of the Golden Age of Athenian culture, in fact, Pericles had done much to destroy the good works of Athens and to sabotage the anti-Persian cause. Pericles broke the alliance of the Delian League and led Greece into the Peloponnesian War, pitting Greek against Greek instead of Greek against Persian.

Under Pericles’ leadership, Athens increasingly became imperialistic and began to experience an agricultural and industrial decline and its economy was suffering for it.

Athens, under Pericles’ direction, responded to this economic crisis not by increasing the emphasis on scientific and industrial advancements but rather on increasing their imperial looting of other Athenian city-states, which increasingly were treated as vassals to Athens.

Sparta was clearly not going to go along with this and this is what broke up the very important alliance of the Delian League leading into the Peloponnesian War.

Pericles actually led Athens into the first two years of the Peloponnesian War against Sparta. So it is clear, Pericles was a massive saboteur of the Greek cause against Persia.

The Peloponnesian War had Greeks fighting Greeks from 431-404 BC, lasting for nearly thirty years.

Pericles is also the one to have introduced the infamous sophists to Athens, which Plato eviscerated throughout his writings, notably the dialogues of Gorgias and Protagoras, not to mention the character of Thrasymachus in his Republic. None of these characters were fictional devices created by Plato, but were in fact leading sophists of their day. In the dialogues, Plato would showcase where these men’s true values and morals lay. In fact, it was Gorgias who was responsible for encouraging Alcibiades to commit to the suicidal run attacking Syracuse which resulted in extending the Peloponnesian War for another thirteen years.

For a price, these foreign sophists would offer any Athenian who wished his children to prosper in the city government, tutoring in the use of rhetoric and “sophistry”, which was simply the art of making a weaker argument appear the stronger. Sophistry promised a fast track to success in government, and was heavily promoted by Pericles’ chief adviser Anaxagoras.

The sophists were not surprisingly also against the anti-Persian cause.

Because Persia had not been successful in their attacks from the outside, the strategy had changed to have Greece destroy itself from within, pitting Greek against Greek.

In 417 BCE Athens was strong enough to bring the war to a close but was subverted by the decisions of one man named Alcibiades. Plato had introduced this Alcibiades in several dialogues as a promising young man that Socrates was attempting to organize, but failed to sway from the influence of the sophists. Alcibiades would heed the advice of Gorgias to invade Syracuse since this would deliver him fame and fortune. Syracuse was known for its vast troves of riches, and at the time Athens was bankrupt, largely from the costly Peloponnesian War.

The Athenians enthusiastically backed the invasion of Syracuse, and paid no heed to their leading general Nikias who is presented in Plato’s dialogue Laches discussing the meaning of courage with Socrates. Alcibiades’ expedition resulted in the decimation of the Athenian army and navy as tens of thousands of Athenians died of starvation in caves as captives of Sicily.

This massive loss was enough to keep the Peloponnesian War going for another 13 years.

Persian subversion had brought the Greeks into a collapse administered by their own hand.

***

Now we enter the timeframe of Plato.

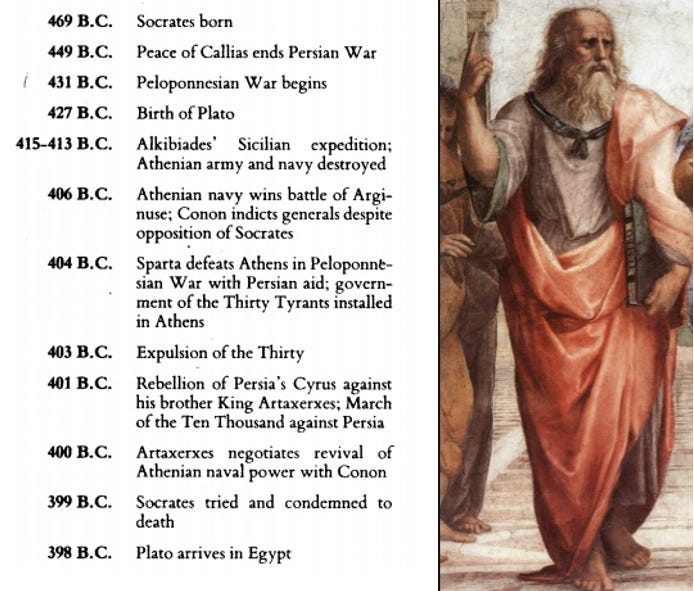

Plato was born in 427 BCE, and thus four years into the Peloponnesian War and is a young man when the war ends in 404 BCE. Athens is considered the loser of the war, however, this had much to do with Admiral Lysander of Sparta who struck an alliance with the Persians sealing Sparta’s victory and ending the conflict.

Subsequently, the Thirty Tyrants, chosen by Lysander, are put in place as the new Athenian government.

Historical accounts say the rule of the Thirty Tyrants, which was only about eight months long, was so horrendous that it made the Peloponnesian War look pale in comparison. Many executions and brutal in-fighting occurred further weakening a defeated Athens.

Plato is living as a young man throughout all of this, and by the age of about twenty meets Socrates, who is among the few leaders remaining of the anti-Persian force. Socrates was, among others, leading the efforts to revive the city-building tradition of Solon.

Socrates’ education in public affairs doubtlessly came from his father, who was a close friend of Aristides the Just, the leader of the Athenian Areopagites (Council of the Areopagus). Socrates was himself closely associated with the Aristides family and acted as ward to Aristide’s granddaughter and tutor to his grandson.

There is a lot of criticism that Plato and Socrates were simply philosophers who did a lot of talking but never participated in the political fight within Athens. This could not be further from the truth.

One example occurred in 406 BCE, two years before the defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian war.

Conon, a leading democratic military man in Athens (and massive stooge of Persia), charged the entire Athenian staff of military Generals with the crime of refusing to pick up shipwrecked soldiers following the Battle of Arginusae. The fact was that doing so amidst stormy waters would have put the rest of the crew at major risk. This was nothing other than an attempted military coup d’état on the part of Conon, who was calling for the execution of all of the leading Athenian military men.

Socrates, who was serving his term in rotation as president of the Athenian Assembly stopped the trial, declaring it in violation of the laws of Athens and refused to put the question to a vote. The democratic party, nonetheless, illegally condemned the Generals to death the following day. The military leadership of Athens was destroyed which paved the way for a Persian-backed Spartan victory over Athens in less than two years.

To give a more personal context of what Plato was being confronted with as a young man here are a few excerpts from his Letter VII.

In my youth I went through the same experience as many other men. I fancied that if, early in life, I became my own master, I should at once embark on a political career. And I found myself confronted with the following occurrences in the public affairs of my own city. The existing constitution being generally condemned, a revolution took place, and fifty-one men came to the front as rulers of the revolutionary government, namely eleven in the city and ten in the Peiraeus-each of these bodies being in charge of the market and municipal matters-while thirty were appointed rulers with full powers over public affairs as a whole. Some of these were relatives and acquaintances of mine, and they at once invited me to share in their doings, as something to which I had a claim. The effect on me was not surprising in the case of a young man. I considered that they would, of course, so manage the State as to bring men out of a bad way of life into a good one. So I watched them very closely to see what they would do.

And seeing, as I did, that in quite a short time they made the former government seem by comparison something precious as gold-for among other things they tried to send a friend of mine, the aged Socrates, whom I should scarcely scruple to describe as the most upright man of that day, with some other persons to carry off one of the citizens by force to execution, in order that, whether he wished it, or not, he might share the guilt of their conduct; but he would not obey them, risking all consequences in preference to becoming a partner in their iniquitous deeds-seeing all these things and others of the same kind on a considerable scale, I disapproved of their proceedings, and withdrew from any connection with the abuses of the time.

Not long after that a revolution terminated the power of the thirty and the form of government as it then was. And once more, though with more hesitation, I began to be moved by the desire to take part in public and political affairs. Well, even in the new government, unsettled as it was, events occurred which one would naturally view with disapproval; and it was not surprising that in a period of revolution excessive penalties were inflicted by some persons on political opponents, though those who had returned from exile at that time showed very considerable forbearance. But once more it happened that some of those in power brought my friend Socrates, whom I have mentioned, to trial before a court of law, laying a most iniquitous charge against him and one most inappropriate in his case: for it was on a charge of impiety that some of them prosecuted and others condemned and executed the very man who would not participate in the iniquitous arrest of one of the friends of the party then in exile, at the time when they themselves were in exile and misfortune.

As I observed these incidents and the men engaged in public affairs, the laws too and the customs, the more closely I examined them and the farther I advanced in life, the more difficult it seemed to me to handle public affairs aright. For it was not possible to be active in politics without friends and trustworthy supporters; and to find these ready to my hand was not an easy matter, since public affairs at Athens were not carried on in accordance with the manners and practices of our fathers; nor was there any ready method by which I could make new friends. The laws too, written and unwritten, were being altered for the worse, and the evil was growing with startling rapidity. The result was that, though at first I had been full of a strong impulse towards political life, as I looked at the course of affairs and saw them being swept in all directions by contending currents, my head finally began to swim; and, though I did not stop looking to see if there was any likelihood of improvement in these symptoms and in the general course of public life, I postponed action till a suitable opportunity should arise. Finally, it became clear to me, with regard to all existing communities, that they were one and all misgoverned. For their laws have got into a state that is almost incurable, except by some extraordinary reform with good luck to support it. And I was forced to say, when praising true philosophy that it is by this that men are enabled to see what justice in public and private life really is. Therefore, I said, there will be no cessation of evils for the sons of men, till either those who are pursuing a right and true philosophy receive sovereign power in the States, or those in power in the States by some dispensation of providence become true philosophers.

What this letter means is that despite the fact that Athenian society had a good constitution, a good foundation that was based off of Solon’s laws, there was nonetheless a degeneration into tyranny, corruption and mob rule.

So Plato is confronted with this and as a young man thinking to himself “What can I do about this?” Already at such a young age, Plato had the ability to see into the distant future and knew that there was nothing he could do in that very moment that could change the outcome which he was trying to prevent. Athens had reached such a point of decay, that the situation called for not only a great intervention but a great deal of work. There needed to be a total educational reform at this point because there was such a crisis in thinking which sophistry had done much to invoke.

It is at this point that Plato decides that this will be his life’s mission. Not as some romanticized idea of revolution, where one needs but lead the masses, for Plato understood that if you did not have a qualified group of thinkers to lead such a revolution, it would only bring about a bloodbath and further mayhem.

In 403 BCE, the Thirty Tyrants are expelled and there is a campaign in 401 BCE for a grouping of anti-Persian Athenian and Spartan forces to support Cyrus the Younger who is the brother of King of Persia Artaxerxes and thus heir to the Persian throne. This campaign became known as the Ten Thousand, mostly made up of Spartan soldiers.

It was hoped that Cyrus the Younger would dethrone Artaxerxes and rule Persia as a continuation of what was believed to be the rightful legacy of Cyrus the Great, a builder of cities, culture and industry and not a destroyer, plunderer or enslaver.

It was Cyrus the Younger’s wish to coexist peacefully with Greece.

Interestingly Xenophon, who is one of the leading students of Socrates (Plato and Xenophon were the two star pupils of Socrates), writes a historical account known as the Anabasis. This is especially relevant since Xenophon is also one of the soldiers of the Ten Thousand that accompanies Cyrus the Younger to fight Artaxerxes in the heart of Persian territory.

Xenophon writes in his Anabasis that he had asked Socrates for his advice and permission to join the expedition, and whether he thought it was a good idea. Xenophon was then sent on an intelligence probe to the Temple of Delphi.

Unfortunately, Cyrus the Younger is killed at the Battle of Cunaxa, after making a fatal decision to enter the fray by himself. The army of Ten Thousand won the battle but lost the war. There was now no hope that a Persian philosopher king could be placed on the Persian throne.

After Cyrus the Younger fell, chaos followed, for it was not clear whether the army should proceed to Babylon anyway or retreat back to Greece to form a contingency plan. Meno who is included in Plato’s dialogue by the same name, organizes for all of the Spartan and Greek Generals as well as all of the Captains of the Ten Thousand to be invited as “guest friends” of Persian soldiers supportive of Cyrus who had been fighting alongside the Greeks. They needed to reach a consensus whether the campaign should continue into Babylon or not.

It should be noted that to the Greeks, a “guest friend” is regarded as sacred promise by the host that no harm will be done so long as those individuals remain as guests, and the breaking of such a pact was considered one of the worst violations of the law of the Gods. But Persians are not Greeks, and the pact was broken. The very Persian men the Spartans and Greeks were fighting alongside in battle for weeks slaughtered the generals in the middle of their meal. And it was Meno who organized all of this with the Persian men.

According to Xenophon, Meno is then sent to Babylon and slowly tortured it is said even longer than any other captive. It is likely that the Persians turned on him, since they thought someone capable of this most dishonorable betrayal was not the kind of man they could ultimately trust.

Meno and Conon were the biggest agents bought by the Persian Empire in Athens at the time.

At this point, the army of Ten Thousand was like a body left headless. Luckily a group of young men step up to take leadership of the disorganized force and Xenophon was among them. Through this new leadership, the ten thousand were led to safe return to Greece through a 1500 mile journey through hostile Persian territory.

In Plato’s Meno dialogue, Meno is referred to as a “guest friend of the great king” which was a polite way of saying a Persian agent and discusses with Socrates whether virtue can be taught. In this dialogue, Socrates shows Meno, how even a child Meno is keeping as a slave can discover the doubling of the square, displaying that the slave child was indeed not the inferior to Meno who was unable to solve the problem. Anytas, who is a close friend of Meno, also appears in the dialogue. It was not lost on Plato that Anytas was the chief accuser of Socrates as a corruptor of the youth, which led to Socrates’s execution.

This is no coincidence, that the traitor Meno is also associated with Anytas the chief accuser of Socrates and hints that much of this organized opposition to Socrates was Persian bought.

In 399 BCE, two years after the fall of Cyrus the Younger, Anytas and two other members of the democratic faction grouped around Admiral Conon, brought charges against Socrates on grounds of impiety and corruption of the youth. Plato writes about Socrates’ trial in the dialogue titled Apology.

Thus the many popular slanders that assert Socrates to be only a detached philosopher or Plato to be a supporter of tyranny are easily disproven when one takes the time to look at their actions in history. And despite Socrates conviction as a “corruptor of the youth” being made in the frenzy of mob rule, he abided by the verdict nonetheless, despite having opportunities to escape from his captivity (where he was kept for over a month), Socrates drank the hemlock which caused his death at the age of seventy-one.

By Socrates accepting such an unjust verdict, it showcased the terrifying injustice that arises out of mob rule (rule by popular opinion) which can easily take the form of a vicious species of tyranny onto itself. When the frenzy of mob rule is at its peak, it is the most destructive form of tyranny that can be unleashed upon a society.

Once Socrates dies, his leading allies flee Athens temporarily, because it is politically too hot for them and they risked also being imprisoned and executed.

Plato leaves for Egypt where he stays for thirteen years.

Even though Egypt was a satrapy of the Persian Empire by 525 BCE, which was conquered by King Cambyses of Persia, Egypt nonetheless had maintained a potent anti-oligarchist, anti-Persian elite. This Egyptian elite was centered in the Amun priesthood. In fact, the Athenian law-giver Solon, the philosopher Pythagoras and the scientist Thales of Miletus (another one of the seven sages alongside Solon) both traveled to Egypt nearly 200 years earlier to consult with the Amun priests.

Plato likely followed Solon’s footsteps to Egypt and during his thirteen year stay was likely involved in a political conspiracy against Persia.

During this time Agesilaus is selected by Lysander (who has been working with the Persians) to inherit the Spartan throne. Agesilaus was thought to be not too bright and thus easy to control and was also partially lame physically. Thus Agesilaus was thought to be great puppet material for the Persians.

However, things did not quite work out that way.

As soon as Agesilaus is named King of Sparta, he fired Lysander as Admiral, takes full command, and turns on his pro-Persia supporters. He then used the battle-ready ten thousand soldiers (that made up the contingent that fought for Cyrus the Younger), still assembled in their camps on the coast of Ionia, to liberate Ionia from Persian rule, rather than subjugate Athens as Lysander had wanted.

Agesilaus meets Xenophon at the coast of Ionia with the Ten Thousand, and Xenophon becomes his advisor, remaining good friends for the rest of their lives. Xenophon was rather adept at military strategy and wrote The Education of Cyrus the Great, a masterpiece on military strategy which became Alexander the Great’s most cherished book, which he carried with him everywhere.

In 395 BCE Agesilaus and the Ten Thousand completely destroy Artaxerxes’ army. Lysander in Sparta and Conon in Athens maneuver to stop Agesilaus’ next move which was to strike at the heart of the Persian Empire in Babylon. They achieved this sabotage by creating a navy blockade in the Aegean Sea, which would have prevented Agesilaus’ return home making the entire military campaign for naught, and causing the Ten Thousand army to run out of resources, left completely vulnerable to a Persian onslaught.

The Cult of Delphi also aided in spreading ominous prophecies and called for the resignation of Sparta’s King, Agesilaus.

Agesilaus’ forces were saved from being cut off from their return route, thanks to the support from the Egyptian component of the anti-Persian alliance, where Plato was on the scene.

The Egyptian navy effectively moved their forces north to the Aegean Sea and forced the Athenian and Spartan navy to stand down, reopening the return route for Agesilaus and his Ten Thousand men.

Lysander’s plot to capture the Spartan throne was thus undone by the priests of Amun (in Egypt) who came forward publicly for the only time in recorded history to denounce the Temple of Apollo and Lysander as conspirators, demanding the expulsion of Lysander from Sparta.

In addition, Egypt’s King Nepherites I (Nefaarud I) gave Sparta, under the leadership of Agesilaus, materials for the production of one hundred ships and 500,000 measures of grain, to withstand any attempted attack by Conon.

Plato’s connection to this campaign can be seen by his principal activity in Egypt, and his collaboration with Eudoxus of Cnidus, one of the most outstanding mathematicians of all time, who he would continue to work closely with during their stay in Tarentum with Eudoxus’s teacher Archytas, the leader of Tarentum. Later Eudoxus’ school would merge with Plato’s Academy.

According to Charles Tate’s paper “The Truth About Plato,” Eudoxus is described by his ancient biographer to be an agent of Agesilaus in Egypt. With Plato and Eudoxus being close political allies, it is safe to say that Plato played a major role politically in organizing the Egyptian support for Agesilaus’s military campaign against the Persians.

Agesilaus, however, would have to wait for his next opportunity against Persia, after a Corinthian War was declared against Sparta before he could continue the operation. This war prevented Sparta from sending its best troops to Asia for Agesilaus’s campaign against Babylon.

The Corinthian War was an ancient Greek conflict lasting from 395 BC until 387 BC, pitting Sparta against a coalition of Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos, backed by the Achaemenid/Persian Empire.

Agesilaus has been recorded in history as having said “I have been driven from Asia by 10,000 archers,” however, he did not mean actual archers, but Persian coin, the Daric, which had showcased Persian archers on them. Agesilaus was referencing the Persian bought city-states of Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos whose declaration of war with Sparta sabotaged his military campaign against Babylon.

In 388 BCE Plato left Egypt and he arrived in Tarentum where he stayed for three years, building an intelligence network with Eudoxus and Archytas where the trio worked on their next game plan.

Despite the Greek and Spartan soldiers being militarily superior to the Persians, the Persians had been very successful in creating internal resistance with the Greek city states against these military campaigns, through bribery and other forms of corruption.

According to Charles Tates’ hypothesis in his “The Truth About Plato,” Plato, Eudoxus, and Archytas decide that they need to first destroy the Temple of Delphi, which was the source of this corruption and counter-intelligence in Greece. By destroying the Temple of Delphi, the source of this pro-Persian financing would be cut off, making it feasible to finally lead a military campaign into the heart of Persia, Babylon.

By the fourth century, Syracuse was the richest city in all of the Mediterranean, and it was decided by Plato, Eudoxus and Archytas, that this was strategically the best base from which to launch their attack.

Unlike the Persian bought Greek city-states (except for Sparta of course), Syracuse was not pro-Persian, and had sided at every instance during the Peloponnesian War on the side of the anti-Persian forces. This is likely why Gorgias encouraged Alcibiades to launch his suicidal run against Syracuse earlier.

Plato enters Syracuse in 387 BCE and meets Dionysus I and tries to organize him to change from being a tyrannical ruler to a lawful philosopher king. Dionysus I was a soft tyrant in relation to others who existed during his time. For instance, despite the many prominent Syracusans exiled under his reign, there is no reliable record to show he ever executed citizens. Being exiled was often only temporary with a return of possessions and citizenship often delivered in time.

Reported by the first century BCE historian Diodorus, Plato had convinced Dionysius I that if he were to liberate Greece he must destroy the Oracle of Apollo of Delphi by military force.

In 385 BCE, Plato was able to organize Dionysus I to begin one of the most ambitious city building projects ever conceived. His plan was to establish cities on the Adriatic Sea, to gain control of the passage between Italy and Greece. With this secured, the route to Epirus on the western coast of mainland Greece would come under Syracusan control. Next Dionysus I planned to use these cities as a military staging ground for a great invasion of Delphi.

With the temple priests destroyed, the financial and political intelligence underpinning of the Persian-backed Theban-led alliance against Sparta would be destroyed. Once freed from battling for its very existence, Sparta led by Agesilaus, and backed with a Syracusan fleet and all the gold captured from Delphi could complete the task begun ten years earlier and end the Persian empire.

However, Dionysus I became convinced by members of his court that Plato was plotting against him, and consigned him to a fate never used against Greeks except in a state of war. Dionysus, a slave of his fears and ignorance, sold Plato into slavery.

Plato is purchased from slavery with the help of Dion the nephew of Dionysius I, who refuses to be paid back. The funds are subsequently used to pay for the building of the Grove of Academus, which later became known as ‘Plato’s Academy’. Eudoxus also brings his school from a city on the Black Sea and merges it with the academy.

Lists of Plato’s students have survived showing that they came from all over Greece and that several women were even included, typically excluded from schools of philosophy.

It was not just an educational center but an intelligence center.

In 367 BCE, almost twenty years after he had auctioned Plato into slavery, Dionysus I suffered the consequences of leading a tyrant’s life and died, under circumstances that strongly suggest poisoning.

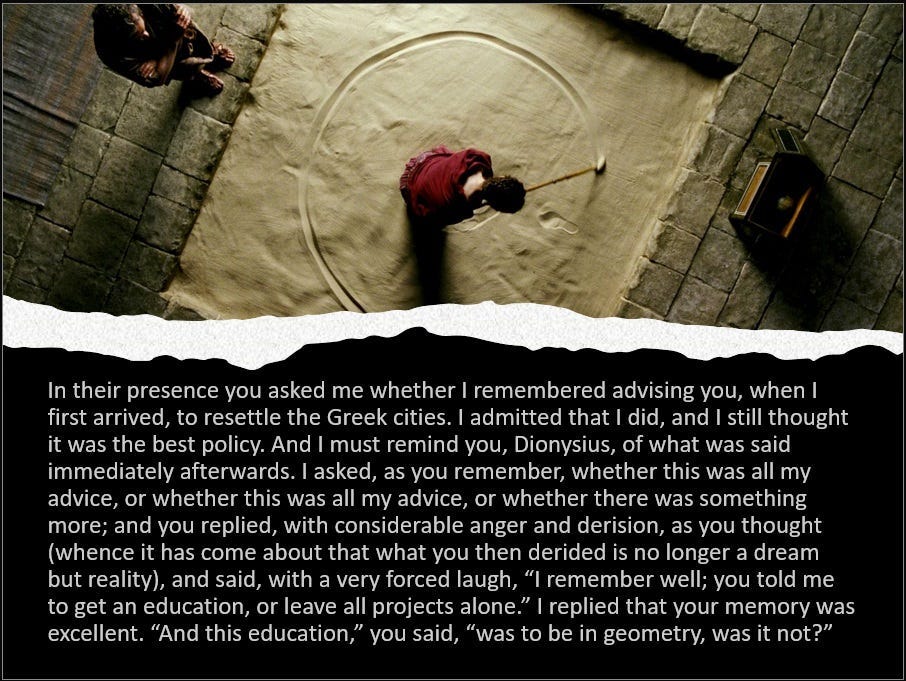

He was succeeded by his son Dionysius II. Dion, the most experience person at court, quickly became the virtual regent of the young man who had just entered his twenties. Dion asked for Plato’s return to Syracuse and immediately began to immerse the boy in a rigorous study of geometry and epistemology, making it clear, that he would never become a great leader of his people if he did not first master these sciences. At first the young man was eager to learn. According to Plutarch the floors were covered with sand and used to sketch geometric constructions.

However, young Dionysus II soon became frustrated with his long hours of studying, and starts to feel like he has been lied to and cheated by Plato, who had promised him great power if he only took the time to commit to his studies.

Below is a recount of this from Plato’s Letters:

At this point, it is getting pretty heated between Dionysus II and Plato, and Plato is kept under house arrest.

Dion is exiled and becomes a student of Plato’s Academy. Syracuse is at war with Carthage within a year, and Plato, who was under house arrest, is able to leave at the outbreak of the war.

Plato then writes his Republic, to which the question of political leadership is fundamentally a question of education. It is here that Plato characterizes the bronze, silver and gold souls, representing individual concern only for personal gratification (bronze souls), the rational individual who strives to conduct his affairs according to existing laws (silver souls), and the individual who functions on the basis of creative reason to better humankind (gold souls).

According to Charles Tate, beginning in 357 BCE Plato’s Academy directed its resources into a two pronged military campaign with the aim that Syracuse was to be seized by Dion and Delphi was to be destroyed by the forces of the native population of Phocis, with aid from Sparta.

The Third Sacred War (356 BCE – 346 BCE) is thus launched between the forces of Thebes and Phocis for control of Delphi.

Dion would eventually take the city of Syracuse, however, less than one year later, in 354 BCE Plato’s ally was assassinated.

The Asia Minor offensive had suffered a crippling setback in 362 BCE when the Spartan king Agesilaus dropped preparations to move his army from Egypt to join the rebel forces. Instead Agesilaus stayed behind in Egypt and militarily supported a rebellion by the Egyptian nobleman Nekht-har-hebi against the successor of Nectanabo I, who had died several months earlier. This rebellion was known as the Satraps’ Revolt.

Not only did Agesilaus’ intervention into the succession cost the Satraps’ Revolt the support of the Spartan Army, but it pulled the troops of Nectanabo’s successor from the side of the other armies in Asia Minor, as the Egyptian Pharaoh rushed home to defend his throne.

As a consequence of the departure of the Egyptian army, Datames withdrew his forces, Orontes had already sold out to the Persians by then and the revolt collapsed.

Agesilaus died at seventy years old, a year later in Egypt.

Amun priests would guide and nurture and then bring into their country a man who would fulfil the ambitions of Agesilaus and finally free Egypt from the Persian domination: Alexander the Great. Asked to explain to the Egyptian people who this great liberator was, it is said Alexander’s soldiers gave the simple answer: “he is the son of Nectanabo.”

Historians Plutarch, Curtius, Justin, and Diodorus all report that Alexander was told upon his visit to the Temple of Amun that Amun, not Philip, was his true father.

According to history records, Alexander was recruited to this program through the embassy of Delius of Ephesus, a student of Plato’s Academy. Throughout Alexander’s career, he was to rely on Plato’s students for his guidance in the extraordinary feat not only of conquering but rebuilding Persia as a humanist empire founded on Greek culture.

This is most clearly shown by him being greatly organized by Xenophon’s The Education of Cyrus the Great.

Alexander did not have complete success, murdered after his conquering of Babylon in his early thirties. However, the cities he had built and through his education of the peoples based on the best of Greek classical culture, he had preserved for later generations the seeds of future renaissances.

In many ways, Alexander the Great was the true continuation of Cyrus the Great, with the important exception that Alexander had a much clearer idea of what was required for a re-education and advancement of culture and civilization.

Alexander the Great would die at a young age, but the accomplishments he would make in the regions that he reconquered from the Persian Empire would continue to have a strong foundation in classical Greek culture, preserving for later generations the basis upon which civilization finds its renewal.

One of the best examples of this legacy of Alexander the Great is the Library of Alexandria.

The city of Alexandria was founded in 331 BCE by Alexander in Egypt.

The Library of Alexandria was founded in around 283 BCE by a Greek, which would stand as a center for knowledge as wisdom for nearly 1,000 years.

Eratosthenes, a Greek, famous for calculating the circumference of the Earth, with just a stick, headed the library starting in 255 BCE.

It is at this point that I would like to end with a few thoughts from Plato’s Theatetus, which is a beautiful dialogue written after the Republic and near the end of Plato’s life. It is a dialogue Socrates has with Theatetus, a young boy on the nature of knowledge and wisdom. In real life, Theatetus showed a lot of promise as a brilliant student in the academy but tragically died in battle as a young man.

Plato writes:

“Nothing ever is but is always becoming.

The result, then, I think, is that we (the active and passive elements) are or become, whichever is the case, in relation to one another, since we are bound to one another; and so if a man says anything “is” he must say it is to or in relation to something, and similarly if he says it “becomes”; he must not say it is or becomes absolutely, nor can he accept such a statement from anyone else.

If perception is knowing how do we have knowledge about the future which we have not perceived yet? This is the foundation for any good statesman and development of statecraft. Where does this wisdom arise from then?

Is it not true then that all sensation which reach the soul through the body can be perceived by human beings and also by animals from the moment of birth whereas reflections about these with

reference to their being and usefulness are acquired if at all with difficulty and slowly through many troubles, in others words through education?

Is it then possible to attain truth for those who cannot even get as far as being? And will a man ever have knowledge of anything in truth of which he fails to attain?

Then knowledge is not in the sensations, but in the process of reasoning about them; for it is possible to apprehend being and truth by reasoning but not by sensation.

Knowledge is thus true opinion when accompanied by reason, but that of unreasoning true opinion is outside of the sphere of knowledge.

Thus excellence is not a gift but a skill that takes practice. We do not act ‘rightly’ because we are born ‘excellent’ but rather, we achieve ‘excellence’ by acting ‘rightly.’”

Cynthia Chung is the President of the Rising Tide Foundation and author of the books “The Shaping of a World Religion” & “The Empire on Which the Black Sun Never Set,” consider supporting her work by making a donation and subscribing to her substack page Through A Glass Darkly.

Also watch for free our RTF Docu-Series “Escaping Calypso’s Island: A Journey Out of Our Green Delusion” and our CP Docu-Series “The Hidden Hand Behind UFOs”.

Thank you for the in-depth historical narrative and links to other sources on Plato.

This is one to print and study. I recently read a few pieces on Akhnaten 1370 BC, so will be anxious to superimpose his amazing life on this chronology. Wow, again, Cynthia. Thanks.