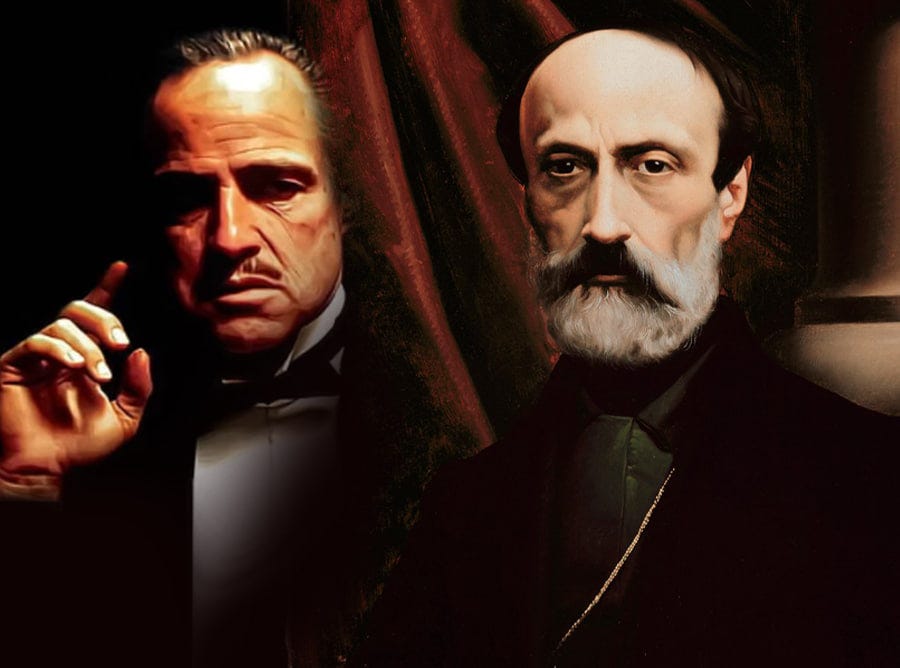

The British Origins of the Jacobins, Mafia Godfather Mazzini and the Rise of the Young Europe Cults

The French Connection: The Knights of Malta, the Scottish Rite & the Rise of the Mafia Brotherhoods Part VI

“Joseph Mazzini, who sixty years ago was a prisoner in Fort Savona for revolutionary speeches and writings, may be looked upon as the chief instigator of modern secret societies in Italy having revolutionary tendencies. The independence and unity of their country, with Rome for its capital, of course were the objects of Young Italy.”

- C.W. Heckethorn “Secret Societies of All Ages” (1875)

This paper will discuss the British origins of the Jacobins, how Mazzini, who was largely a continuation of the Jacobin phenomenon would have direct British backing and funding in order to form his Young Europe Cults. We will also discuss how Mazzini became the one and only Godfather to the Sicilian Mafia which functioned as his own assassination bureau, along with his Young Italy network. We will also discuss how the very word Mafia, was a word created by Mazzini himself as their Godfather.

[This is Part VI of this series. Refer here for Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V.]

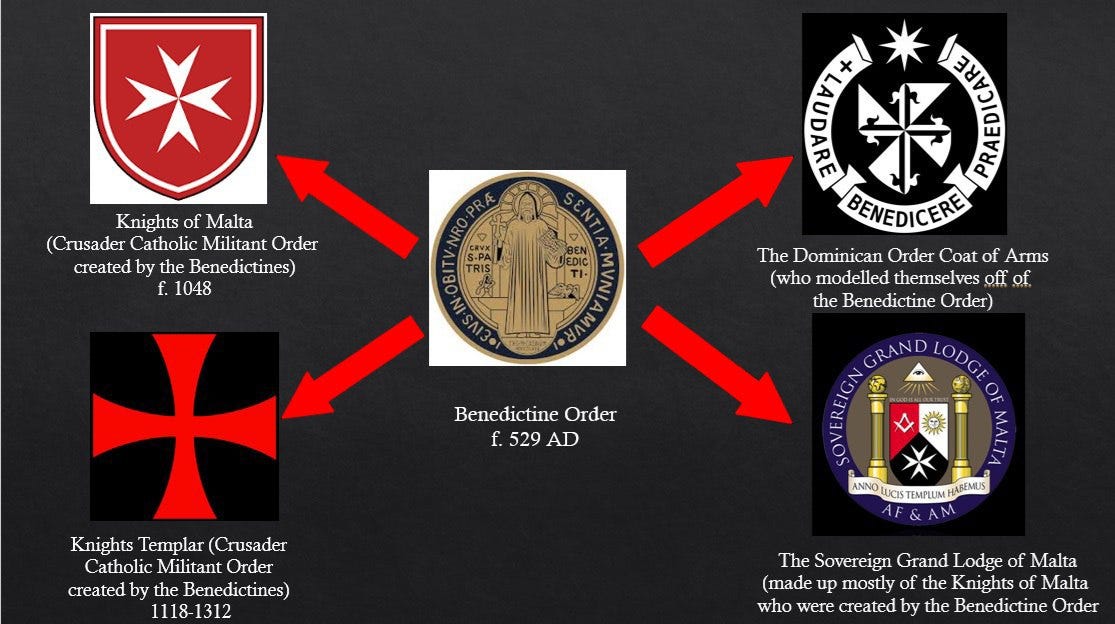

In the previous section, “The Dominican Connection – From the Spanish Inquisition and the Crusades to the Jacobins,” we left off on the observation that the famous French Jacobins of the French Revolution - had in fact taken their name from the Dominicans!

The Dominican Order is a French Catholic order. Their first base was established in Paris in 1218 under the leadership of Pierre Seilhan (or Seila) in the Chapelle Saint-Jacques, on the street of Saint-Jacques - this is why the Dominicans were called Jacobins in Paris.

Yes, it was the Dominicans who were first referred to as Jacobins in Paris.

When the Jacobins of the French Revolution would be burgeoning as a new “club” - to accommodate growing membership, the group rented for its meetings the refectory of the Dominican monastery of the “Jacobins” in the Rue Saint-Honoré, adjacent to the seat of the Assembly.

This is highly unusual and suspect to say the least. For the Dominicans to rent out one of their monasteries, not to mention, the very monastery that was their origin and base in France is a decision that had to be passed at the highest level of the powerful and influential order.

For the Catholic Dominican Order to rent their base to the burgeoning Jacobins, who did not seem like friends to the Catholic Church and its institutions, was a most strange decision indeed.

And it appears that the relationship did not stop at the Jacobins of the French Revolution merely renting a building from the Dominicans, since again most strangely, they decided to adopt the very name of the Dominicans in reference to their society.

Although there are apologists out there who try to claim that the nickname “Jacobins” was given by their opposition, since at the time it was well known to be in reference to the French Dominicans, and thus was no secret - this does not quite pan out as solid reasoning since the Jacobins themselves would promote their name as the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality, and after 1792, commonly referred to themselves as simply the Jacobin Club. Thus, it is clear, the Jacobins very much wished to be referred to in reference to the Dominican Order.

The Jacobins of the French Revolution would also use the former headquarters and fortress of the Templars as their prison during the Reign of Terror where many gruesome tortures were no doubt committed.

One cannot help but wonder how similar the Reign of Terror was to the Inquisitions, all the more interesting when we know where the origin of the name Jacobin comes from and the central role the Dominicans played in said Inquisitions...

Recall the quote from Pierre Mollier where he writes in his paper “Malta, the Knights, and Freemasonry. Ritual, Secrecy, and Civil Society”:

“…[a] more subtle and even more mysterious motive further explains the presence of knights [Hospitaller of St. John of Jerusalem] in [the Malta Freemasonry] Lodges: some showed a clear interest in Christian esotericism. We will not retrace the relations between Loras and Cagliostro here. However, it is also unusual to observe the relative over-representation of the Maltese in Lodges professing the Rectified Scottish Rite: Chefdebien in Narbonne, Aigrefeuille in Montpellier then in Paris, du Bourg and Guibertin Toulouse, La Croix de Sayve in Grenoble, Monspey in Lyon…”

Thus, the “over-representation of Maltese Lodges” who “profess[ed] the Rectified Scottish Rite” had a heavy presence in Narbonne, Montpellier, Paris, Toulouse, Grenoble and Lyon - all French cities.

Recall in Part I of this series that one of the Knights of Malta, Formosa de Fremeaux, a Maltese nobleman who was the Dutch Consolate - was an influential and powerful supporter of the Jacobins as well as the French occupation of Malta.

Thus, the Jacobins would strangely be tied to the Dominican Order, as well as the Templars, Knights of St John of Jerusalem (aka Knights of Malta) and the Maltese Scottish Rite Freemasonic Lodges - and thus spirits of ghosts past of the Crusades and the Inquisitions - in how they would gain power and influence during their Reign of Terror that would end the French Revolution. [See Part V]

But the strange connections would not end there for the Jacobins likely would have never existed if it were not for the British.

The British Origins of the Jacobins

Micah Alpaugh writes in his “The British Origins of the French Jacobins Radical Sociability and the Development of Political Club Networks 1787-1793”:[1]

“Most significantly, in November 1789, correspondence from the London Revolution Society directly inspired the founding of the Paris Jacobin Club, and the integrated national network the Jacobins formed consciously built from British designs.

By 1792, active experimentation proliferated in both nations as the Jacobins radicalized, and their example boomeranged to motivate the creation of a more integrated radical political network in Britain, the London Corresponding Society.

... On 25 November 1789, the French National Assembly heard the session’s President read a letter from the British club, which ‘distaining National partialities’, declared its approbation of France’s revolution and ‘the prospect it gives to the two first Kingdoms in the World of a common participation in the blessings of Civil and Religious Liberty’. By asserting the ‘inalienable rights of mankind’, revolution could make ‘the World free and happy’.

The address produced a ‘great sensation’ and loud applause in the Assembly, which wrote back to London declaring how it had seen ‘the aurora of the beautiful day’ when the two nations could put aside their differences and ‘contract an intimate liaison by the similarity of their opinions, and by their common enthusiasm for liberty’.

Within a week, growing Anglophilia helped provide the impetus for the founding of Paris’s own Societe de la Revolution, which in January 1790 finally adopted the better known title of Societe des amis de la Constitution, retaining the English-style nickname Club des Jacobins.”

Thus, not only did the London Revolution Society help to directly inspire the founding of the Paris Jacobin Club, but also the very network they would build throughout France would use British designs. The Jacobins would stay in close contact with not only the London Revolution Society (but as we will see) various other British institutions throughout their entire existence.

Micah Alpaugh continues:

“Early French Jacobins created their network in consultation with British models, whose power the ‘British Jacobins’ from 1792 onwards would seek to reapply at home…[Thus, the] British and French radical movements were in many respects mutually constituting, providing inspiration and examples for each other at key junctures.

…In a rare surviving founding document, the Jacobins of Strasbourg, in their January 1790 Act of Union, described their organization as founded on the model of the Paris Societe de la Revolution, created in turn ‘on the inspiration of that established in London’…Early Jacobins saw not just a common name, but a direct connection between French and British clubs.

…Certain Jacobin clubs – such as those of Cherbourg and Albi – grew directly out of literary groups. Even these types of organizations, however, had English origins: Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopedie traced the existence of formal scientific societies to the Royal Society of London, chartered by Charles II, as the first occasion when philosophers could ‘assemble themselves to search for truths in peace’, an arrangement spreading to France only several decades later.”

Researcher Tracy Twyman wrote of the Rosicrucian roots of London’s Royal Society: “Most of the members of the Royal Society were Freemasons, and most coupled their scholarly pursuits with esoteric ones, making the Royal Society appear to be much like the ‘Invisible College’ which Robert Boyle, one of the society’s most prominent members, had previously described. He became an even more prominent member of the society after 1668”.

The Invisible College was run as an esoteric society of Rosicrucian Kaballists that took over control of the English government after the ill fated republican government had fallen and the monarchy was restored in 1649. As noted in the previous chapter of this series, Rosicrucianism was inextricably linked to esoteric groups that were created around Benedictine, and Dominican fronts in the early renaissance period.

Micah Alpaugh writes:

“…French clubs concurrently corresponded with the London Revolution Society in progressively greater numbers. The earliest communication, from Dijon’s already- established Club patriotique was sent on 30 November 1789 only five days after the reading of the Revolution Society’s address in the National Assembly. ‘Why do we worry about admitting’, the letter began, ‘that the Revolution which is operating today in our country is due above all to the example that England has offered us over the last century?’ The Dijon club declared that, through their development of constitutional government, ‘the happiness of the English has prepared that of the universe’.

Over the following year 23 addresses to the Revolution Society arrived from clubs across France, many thanking the Londoners for inspiring them to found their clubs. The Strasbourg Jacobins declared that the ‘example of your honourable Society has given birth to all the Amis de la Constitution’. The Amiens club referred to the Revolution Society as a ‘monument of English liberty’, which led ‘Our Revolution to look to form on your model a thousand societies animated by the same ardour and spirit’. Aix-en-Provence’s Jacobins credited the London society with ‘believing in the idea of establishing these societies which multiply in France today’. The Jacobins of La Rochelle, a town with a long history of Catholic-Protestant infighting, now declared that the English and French would ‘follow the same principles. . . carrying the flame of philosophy into regions that superstition and despotism still cover in shadows’. In attempting to break with the past and establish broad new fraternal alliances, numerous French clubs appeared both cognizant of the British origins of their associations, and attempted to develop contact further.

The ideal of an integrated patriotic national club network for both fraternal mobilization and spreading intelligence was of recognized British origin. The French system would seek to build upon this model. Beyond simple recognition, French clubs also sought both instruction from and collaboration with their British counterparts. The Montpellier Jacobins entered into active correspondence with London less than a month after their founding, generating excited correspondence from across their region. ‘We can only applaud’, wrote the Jacobins of Marseille to Montpellier on 1 October 1790, ‘your project of corresponding with the friends of the Revolution in England, and with foreigners in Paris. We owe our union to these close-knit brothers who before us conquered their liberty. We have asked for affiliation and correspondence ourselves’.”

We should recall from Part V of this series, that Montpellier was one of the French cities that were “over-represented” by Maltese Lodges professing the Rectified Scottish Rite – probably not a coincidence…

With the British having become exemplars for hundreds of French clubs, an active exchange of letters and ideas began to influence and help form the Jacobin networks.

Thus, it should be most clear by now that the French Jacobin clubs modelled themselves off of British designs and were aware of this.

Having the privilege of knowing how this story ends - that the Jacobins were responsible for the sabotage of the French Revolution, the years of bloody terror and introduction of Napoleon as a “restorer of order” in France, one cannot help wonder if this outcome was not Britain’s true intention behind the empire’s uncharacteristic “support for liberty” the entire time?

All of Europe (as well as many other parts of the world) had been inspired by the example of the Americans in their Revolution. It was, at the time (in modern history) the only revolution to have successfully won against not just an empire, but the most powerful empire in the world (and possibly ever historically).

For many reasons, France was regarded as the natural follower of the republican example. It was France after all who sent their military to the United States to help fight against the British. Marquis Lafayette who was a war hero of the American Revolution returned to France asking that she too free herself of imperialism.

Recall the French Revolution’s phrase was “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity.” However, one of the tragedies of the French Revolution was that, unlike with the American Revolution, it became more of a class dispute and quickly the poor blamed anyone of an upper class as being the sole problems of that society. They wanted equality by force and by name rather than by earned merit. It was an idea of equality where everyone would be torn down rather than built up, and was not built on the basis of equal opportunity as was the ideal in the American example. Though there should always be a respectable standard of welfare in a responsible republic - it doesn’t mean everybody should receive an equal economic outcome in society no matter what their actions are.

The French Revolution soon devolved into a mob situation, where they had over 40,000 executions including of their artists and their scientists- so of their best minds. It made sense that their best minds were the ones who were best educated and the ones who were able to have access to that education were primarily members of the upper class who had more wealth and opportunity. So instead of realizing that equal opportunity for education was at one of the cores for equal opportunities as citizens, the mob instead attacked those who were educated. Recall from Part IV of this series, how one of the slogans of the French Revolution, thanks to the Jacobins was “The revolution has no need for scientists.”

This was a direct attack on France’s nation state legacy, France was the first in the world to create a nation-state under the great king Louis XI, and this allowed France to be at the head of scientific thought for centuries. France had created the best universities and those best scientific minds of France were at the cutting edge of their fields revolutionizing all fields of human knowledge.

It was this legacy that the Jacobins chose to burn down.

Does that sound like something that would in fact empower or disempower France as a republic? And the fact that the Jacobins were heavily influenced, if not receiving a good deal of their instruction from the British, should make one wonder as to whether this was the intention all along.

Jeffrey Steinberg writes in “The Bestial British Intelligence of Shelburne and Bentham”:

“From the outset, the Jacobin Terror was a British East India Company- British Foreign Office orchestrated affair. The bloody massacre of France’s scientific elite was systemically carried out by French hands, manning French guillotines, but guided by British strings.

Jacques Necker, a Geneva born, Protestant, slavishly pro-British banker, had been installed through the efforts of Shelburne’s leading ally in France, Philippe Duke of Orleans, as finance minister.

…Although Necker failed to block France from allying with the Americans during the American revolution, he did succeed in presiding over the depletion of the French treasury and the collapse of its credit system.

Economic crisis across France was the precondition for political chaos and insurrection, and Shelburne readied the projected destabilization by creating a “radical writer’s shop” at Bowood staffed by Bentham, the Genevan Etienne Dumont, and the Englishman Samuel Romilly. Speeches were prepared by Bentham and translated and transported by diplomatic pouch and other manes to Paris, where leaders of the Jacobin Terror, Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Jacques Danton, and Maximilien de Robespierre delivered the fiery oratories. Records of East India Company payments to these leading Jacobins are still on file at the British Museum.”

Thus, the leaders of the Jacobins not only had their speeches written by Jeremy Bentham but were salaried by the British East India Company!

Steinberg continues:

“Bentham was so taken up with the events in France, that on Nov 25, 1791, he wrote to National Assemblyman J.P. Garran offering to move to Paris to take charge of the penal system. Enclosing a draft of his Panopticon proposal, Bentham wrote ‘Allow me to construct a prison on this model – I will be the jailer. You will see by the memoire, this jailer will have no salary – will cost nothing to the nation. The more I reflect, the more it appears to me that the execution of the project should be in the hands of the inventor.’

At the same time, Bentham was proposing to assume the post of chief jailer of the Jacobin Terror, which sent many of France’s greatest scientists and pro-American republicans to the guillotine or to prison. Bentham made no bones about his loyalties: In accepting the honorary title of Citizen of France, Bentham wrote to the Jacobin interior minister in October 1792: ‘I should think myself a weak reasoner and a bad citizen, were I not, though a royalist in London, a republican in Paris’.”

What this meant was that was Bentham was doing in France, in supporting the Jacobin led French Revolution, was something he was happy to do in France - but not in England, for he would forever be loyal to the British Monarchy and her world empire. Hmmmm.